Story Cycle

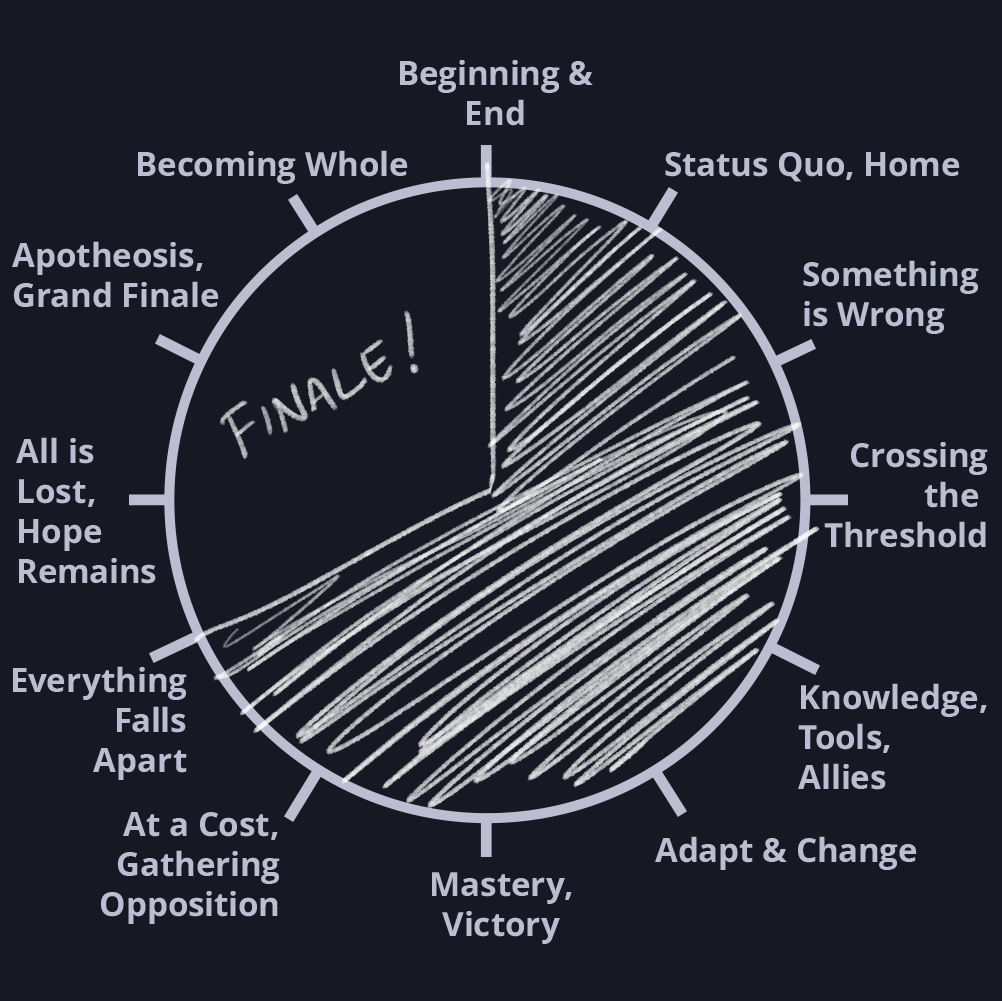

Another way to look at the 12 spokes in the Groovelet Portable Mythology is by assigning each spoke a different role in the story cycle.

- Zariel - beginning and end

- Oth - a zone of comfort, the mundane world

- Cystam - something isn't right, call to action

- Kiro - crossing the threshold into the new and exciting

- Stacks - gaining knowledge, tools, and allies

- Mersenne - adapt to the new world

- World - mastering the new world, false victory, the goal achieved

- Path - the cost of victory becomes apparent, gathering troubles

- Curopal - the twist, betrayal, everything falls apart

- Blit - the darkest before the dawn, return to the familiar, a hope spot

- Audient - the grand showdown, climax and apotheosis

- Misk - master of both worlds, returning and becoming whole

- Zariel - beginning and end

What in the World is This?

You may already be familiar.

It's a pretty obvious reframing of the Hero's Journey, a common template for stories!

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949)

The idea that the hero's journey is common to all stories is, of course, total and complete bunkum. Not every story needs to be structured this way. This is, however, a common and practical way to build a story.

One's exact level of adherence to the formula can vary widely. Some treatments of this, for example, the extremely famous Save the Cat!: The Last Book on Screenwriting You'll Ever Need1 lays out the structure of your ideal screenplay down to the page, including an A plot and B plot.

I'll also point out that this was not, in fact, the only book on screenwriting I felt necessary.

The B story begins on page 30. And the B story of most screenplays is "the love story."

Blake Snyder, "Save the Cat!: The Last Book on Screenwriting You'll Ever Need

On the other hand, Dan Harmon's Story Structure 101: Super Basic Shit contains an extreme short-hand version of the monomyth, an 8-step clock that boils stories down to 8 simple steps:

- A character is in a zone of comfort,

- But they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation,

- Adapt to it,

- Get what they wanted,

- Pay a heavy price for it,

- Then return to their familiar situation,

- Having changed.

Dan Harmon, "Story Structure 101: Super Basic Shit"

and then, to try and make it stick, boils it down to just 8 words:

- You

- Need

- Go

- Search

- Find

- Take

- Return

- CHANGE

Dan Harmon, "Story Structure 103: Let's Simplify Before Moving On"

A Few Words on Writing

This story cycle thing exists within a huge and often contradictory maelstrom of wild and divergent writing advice that exists.

Regurgitating it all here would be, uh, beyond the scope of this simple guide.

Plus: all of my story-writing advice is second hand! While I've read a lot on the topic of writing, I've written few stories and zero successful ones.

behold, the nook of shame

Nevertheless, I've included some notes and ideas to help with structuring a story this way - if anything partially because I, myself, learn things best by attempting to explain them to others.

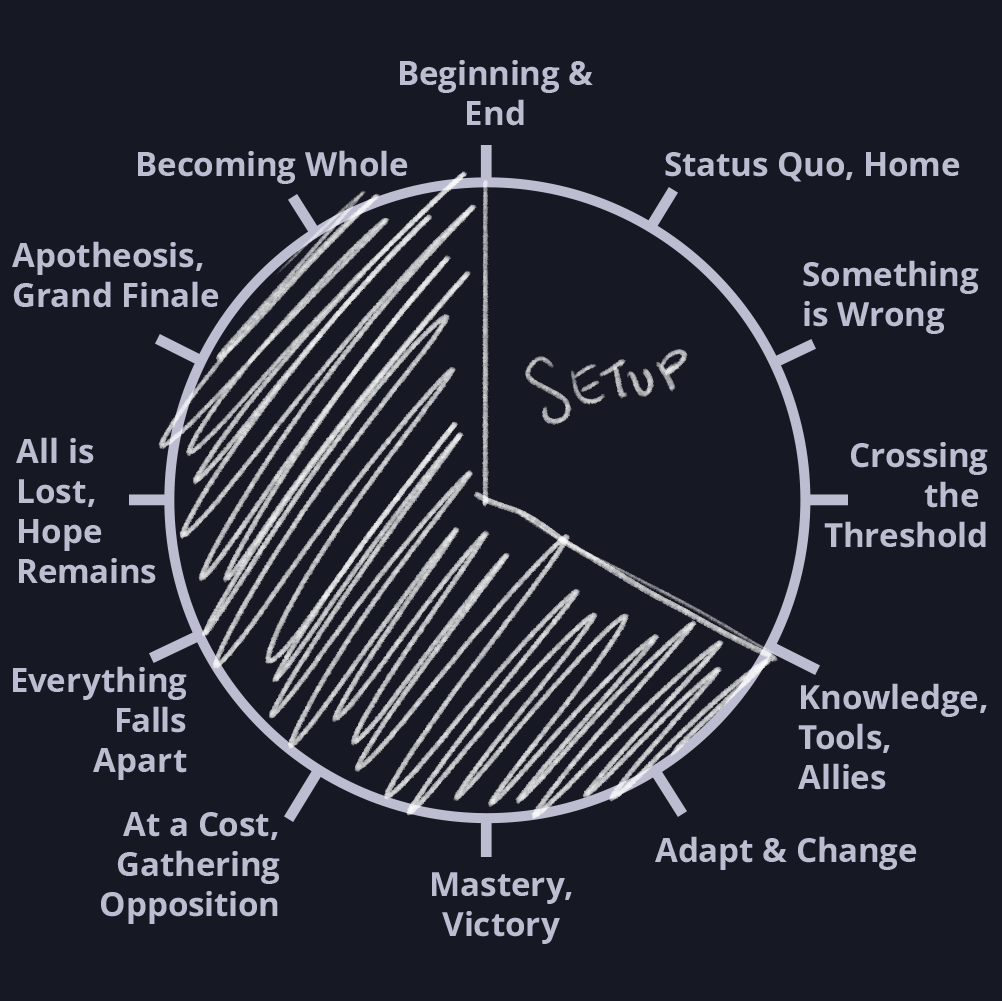

This Structure Divides Cleanly Messily into Three Acts.

That's right, the story wheel is also three act structure.

Three phases:

- Act 1: Setup

- Act 2: Development

- Act 3: Resolution

Act 1. The First Third

Let's get this story started! The First Act is comprised of our first four story beats:

- a zone of comfort, the mundane real world

- something isn't right, call to action, examining the threshold

- crossing the threshold into the new and exciting

- gaining knowledge, tools, and allies

Before we dig into the individual sections, let's talk about some of our goals in this act.

Genre, Characters, Themes, Arcs, and Promises: The First Act

Genre: What's This All About?

An important thing to do up-front is establish what kind of story this is. Is this a science fiction romance or a hard-boiled detective horror story? All of these details should be readily apparent up-front.

One of the reasons so many stories start in medias res, with an opening scene that takes place in the middle of the plot, OR with a prologue that's evocative of the story but not clearly related to the plot until much later - is because this is a way to tell the audience "this is what you're in for". The tone of your opening should match the tone of the entire project. 1

This is derived from advice from Brandon Sanderson's writing lecture series, and he is a writer in a genre that requires a lot of buy-in, but you're looking at a story fantastical enough that it has an enormously elaborate color-mapped pantheon/magic system so the advice probably also applies here.

But The Wheel Starts with "Status Quo"!

Yeah! Life is a series of infuriating contradictions. It is really hard to establish "this is a kick-ass high-stakes science fiction space opera" with some mundane guy farming space-onions on Planet Snoozefest. We can get to Planet Snoozefest shortly, first we need to do something to draw people in to the genre itself.

If this is a heist story, let's show off some heisting! If this is a comedy romance story, let's start with some comedy and romance.

Characters: Who's This All About?

Conventionally, the first viewpoint character introduced is going to be understood as the protagonist and the main character of the story1.

There's some leeway, I think, if you're doing the prologue thing I mentioned in the last segment, but not much.

Generally: Introduce Characters in the First Act

While each of the characterizations and elements are chosen with the archetype's position in the story circle in mind, it probably wouldn't make a lot of sense for the story to be divided equally into 12 parts, each introducing a new specific character1.

See also: the Dire Warning in the Characterization chapter

Characters might also have traits that make them representative of points in the story cycle, but by and large, as a rule of thumb, most of your characters should already be in place by the first third of the story.

If there are characters who haven't been introduced directly, someone should have at least mentioned their name out loud or alluded to their existence.

Arcs and Promises

Brandon Sanderson, famously one of the more successful fantasy writers alive at time of writing, is fond of his theory that a large portion of the writers' job is to establish and then fulfill promises1.

A "promise" is anything that you set up that the audience will want to see paid off.

A Character Arc is a kind of promise that the author makes to their audience: it establishes a question about a character, and the answer to that question is the pay off that the audience has been promised. The characterization chapter lays out some potential dramatic questions for each character archetype, and if the story starts to ask these questions then it is important to answer them.2

This also leads back to the warning about twists - a sudden surprising, shocking twist doesn't fulfill any kind of promise. On the other hand, if the plot is leaving enigmatic clues all through the story, the promise is that these clues will lead to some kind of satisfying revelation that makes them all make sense. That revelation can come as a shock or twist while also fulfilling the promise made by the enigmatic clues that lead to that revelation.

Even a "genre moment" opener is a kind of promise: it promises that the rest of the work is going to be like this.

This is also advice from Brandon Sanderson's writing lecture series. Strong recommend. He's not a writer who focuses on the story circle as part of his process, not as far as I can tell, and presents a completely different theory of structure that's clearly also very effective.

The answer doesn't have to be happy or positive, but it has to be answered.

Theme: What is this Really All About?

Ultimately, the primary dramatic question faced by the protagonist is the crux of the whole story. If the story is about the main character's coming to terms with the idea that morality and legality are not the same thing then the rest of the story can adapt to better flesh out and illustrate that core theme.

Stories can have more than one theme, or in the case of many pulpy novels, no themes at all except "some exciting stuff is going to happen, hold on to your hat".

When developing characters, an interesting question to ask is: how do they provide a unique viewpoint on one of the story's core themes?

In our example: morality vs. legality - characters who might provide thematic resonance include:

- People who have committed crimes for just or good reasons.

- A genuinely terrible person who commits crimes wantonly.

- A genuinely terrible person who follows the law perfectly and precisely.

- People who have committed crimes of desperation.

- A judge who casually interprets the law in whichever way benefits them the most.

- A lobbyist responsible for greasing the palms of the people who write legislation.

This can be a powerful way to plot a story. Be wary, though: too slavishly adhering to this guideline can leave a story feeling stiff and didactic, like a thinly disguised moral story. It's enough to explore an idea from a lot of different angles: the moment you feel like you're preaching it's time to back off a little bit.

Motivations: What Makes Characters Dynamic?

Nobody likes a lump who just lets the plot happen around them. Ensure characters have things that they want to accomplish and are taking concrete action to make those things happen.

That alone is enough to make a lot of characters interesting - even if an antagonist is kicking puppies left and right, that still constitutes motivation and action and makes them attention grabbing.

0/12. Zariel - beginnings and endings

The "cool genre moment prologue" might live here, in the beginnings bin.

Save the Cat argues that the beginning and ending of a story should be echoes of one another, mirror images reflecting the protagonist in their initial and final state. I think this is advice that has mostly fallen by the wayside in the intervening years but it's an interesting idea.

1. Oth - a zone of comfort, the mundane world

Our protagonist exists in a comfortable-enough position. While their world is... okay, it's small, and unsatisfying in some key ways.

This would be a wonderful time for the protagonist to twirl on a hill and sing an "I Want" song.

2. Cystam - something isn't right, call to action

Something is drawing our protagonist into a new and exciting world - maybe their own motivation, maybe some external force beckoning them.

3. Kiro - crossing the threshold into the new and exciting

There's a firm dividing line between the mundane world the protagonist is leaving behind and this new and exciting world, and they make the decision to break through and enter the new world.

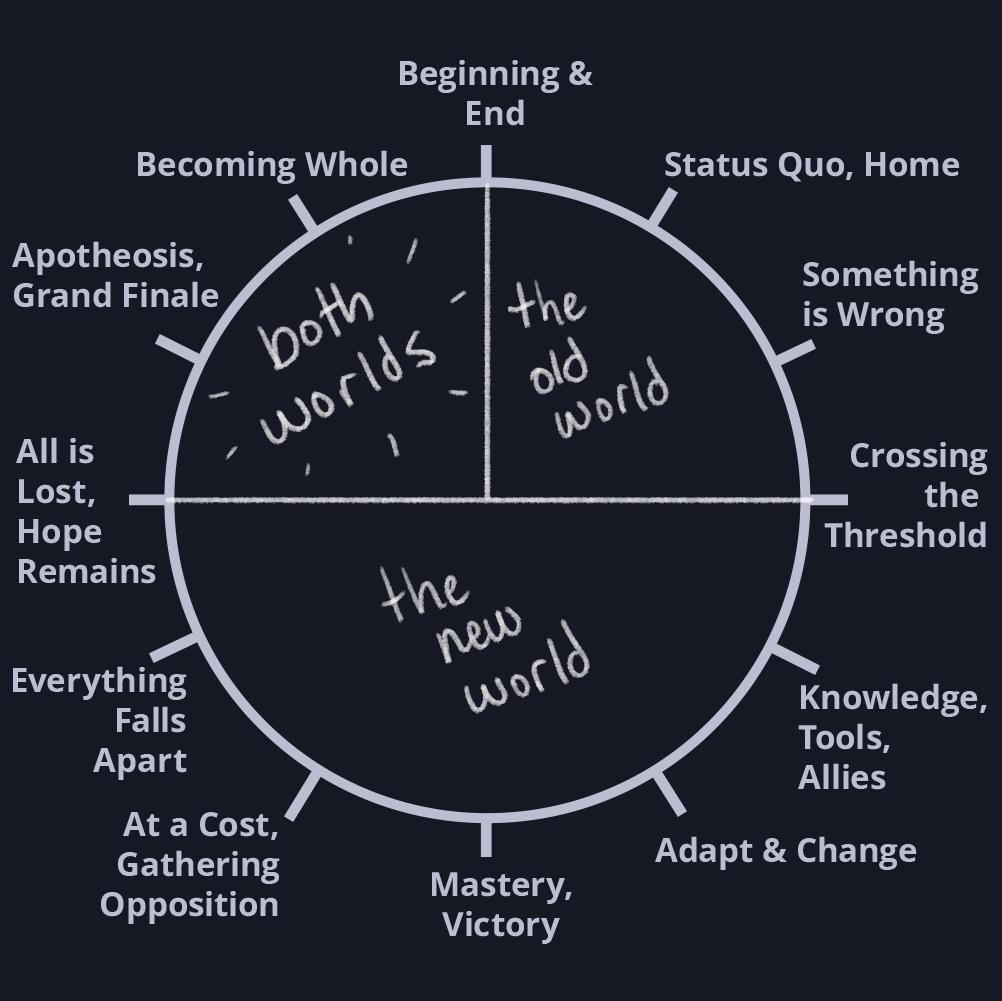

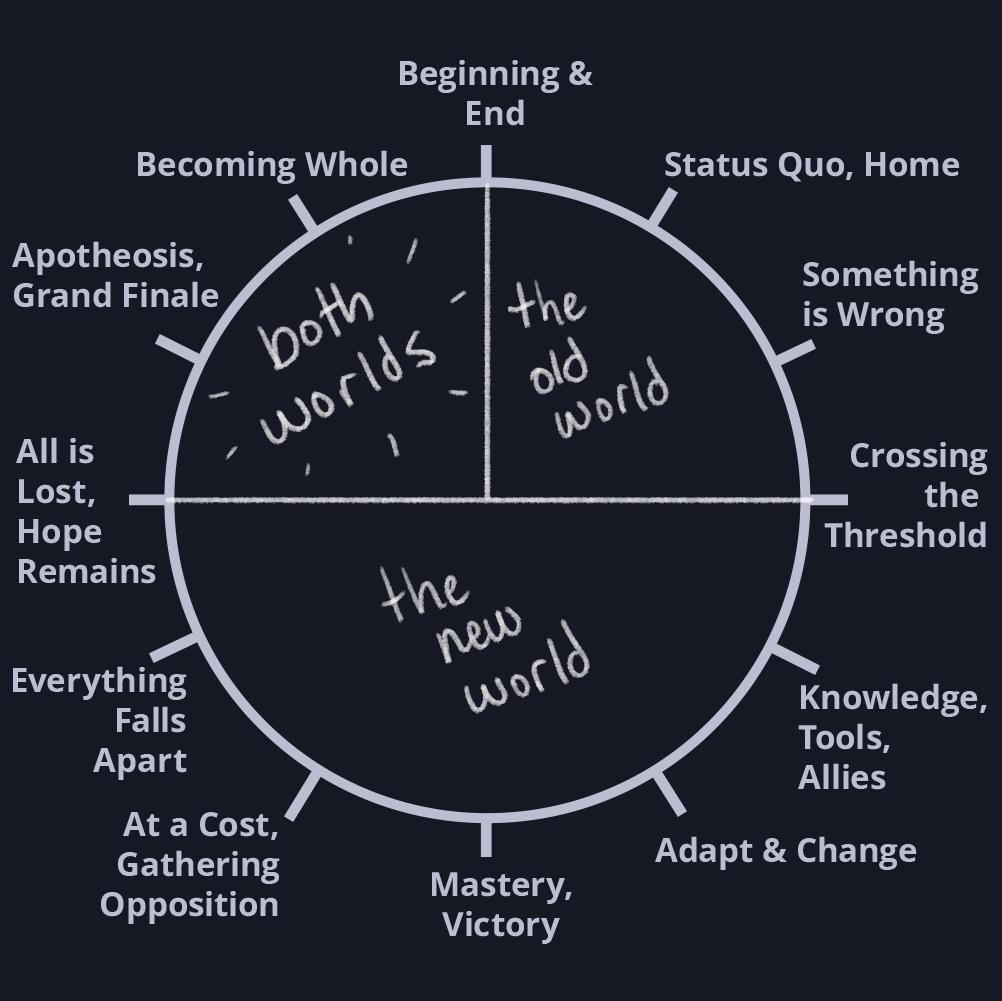

The Old World and the New World

"Wait, what do you mean by new, exciting world?"

So, part of the Hero's Journey, the story cycle, this model in general is that it focuses on going somewhere.

Like, cracking through a wardrobe and popping out in Narnia.

At its very simplest, the story cycle is a tale of our protagonist going to a place, having an adventure, learning a thing, and coming home, having learned something new.

So the "new world" is whatever place our protagonist has to GO to have this adventure.

The New World Doesn't Literally Have To Be A Place

A lot of ink has been spilled about this "new world" in story terms. It's the unconscious, it's adventure, it's the thing that our protagonist is tackling.

The thing is, the idea of a "new world" is very flexible. If I wrote a story about my journey to the bank, "the bank" could be the exciting new world, and the threshold might literally be the door to the bank. I'd return... having change.

In magical fantasy stories, the "new world" can be very literal, and the contrast between the old world and the new world can be really stark - Dorothy getting house-dropped into Oz, and the whole black-and-white film erupts into color1.

In more grounded, realistic stories, the "new world" can be as simple as "helping to plan a wedding for my daughter", and crossing the threshold can be "deciding to help to plan a wedding for my daughter"2.

I'm sure in 1939 this was cool as hell. Honestly it's still a really bold and effective stylistic choice, almost a hundred years later.

The movie "Father of the Bride" (1991) didn't make nearly as many bold and effective stylistic choices.

4. Stacks - gaining knowledge, tools, and allies

Freshly in the new world, the protagonist must learn how to succeed in this new environment. We meet friends, gain skills, learn how the new world works.

Beat Shuffling, and The Journey into A Dangerous World

One of the serious problems of any of the story circle ways of exploring and developing a story is that it has a problem: it seems like a one-way ride, chunk chunk chunk, you do the mundane world, you do the call to action, you cross the threshold, there you go.

It's actually a struggle to find media this rote. Even in stories that thoroughly embrace the idea of the Hero's Journey, scenes and structure are a lot more flexible than this. The Matrix starts with a call to action, then moves to an exploration of the mundane world: how dare the Sisters Wachowski play the notes out of order! But it works fine.

The overarching goals of the first act are to have the protagonist choose a dangerous new world, contrast that dangerous new world with their normal existence, give them tools and allies that they can use to succeed, and establish characters, motivations, themes, arcs, and promises for the rest of the story to develop: the exact order of operations here is not as important so long as everything fits together.

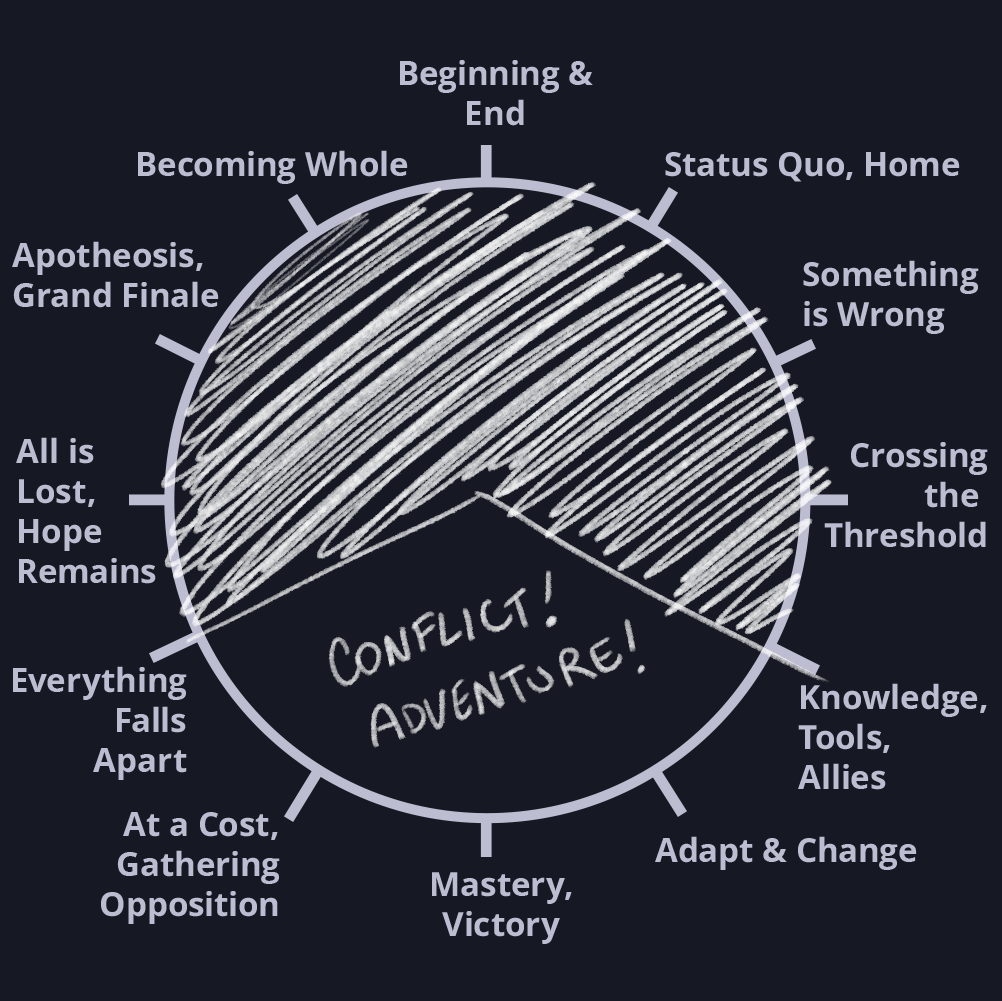

Act 2. The Second Third.

The goals of this act are to really lean into the conflict. The protagonist will try, again and again, to resolve the story, and they will succeed somewhat, but ultimately fail. 1

If the protagonist has a really good second act, panic immediately, you are in a tragic story, things are about to go badly off the rails.

4. Stacks - gaining knowledge, tools, and allies (again)

You know what? I'm going to say something that's going to get me thrown out of all of the stuffiest creative writing circles.1

The "gaining knowledge, tools, and allies" beat can comfortably go pretty much anywhere in Act 1 or Act 2. It belongs to both Act 1 and Act 2.

It's a floating beat. And it can happen multiple times!

Also: a character simply displaying knowledge that they already have is the same as "gaining knowledge" from the perspective of the audience.

It's okay, I don't actually belong to any. All of my friends are software developers. All of them. We mostly talk about the intricacies of board game rule systems and git.

5. Mersenne - adapt to the new world

This new world is confusing and difficult, and our protagonist will start out weak and ineffective, but gradually grow and change to adapt to the new world - while at the same time they might cause the new world to grow and change to adapt to them.

A Nested Calculus of Problem and Solution

Many authors find the middle of a book to be the hardest part. There are so many things that have to be set up in Act 1 that there feels like a lot of structure, but then the middle of our story is this formless goop of "gettin' better, learnin' lessons, solvin' problems" which can feel kind of directionless to write at.

The goal here is something of a cycle: setback, then solution, setback, then solution, as we work our way towards a goal.

There are a few ways I've seen of addressing this: Dan Harmon's story circle theory is simply that each sub-problem encountered is its own, fully-realized microcosm of the whole story cycle.

Brandon Sanderson pitches a theory of opening and closing nested problems, like opening and closing parentheses. This is a very satisfying model for math nerds and programmers. So, let's say we have a problem and a solution:

( We have to get to the castle

We get to the castle )

We can then create a problem, or sub-problems, within that problem:

( We have to get to the castle

(There is a forest in front of the castle

We traverse the forest)

(There is a moat in front of the castle

We construct a bridge to cross the moat)

We get to the castle )

And then we can create sub-problems within those problems:

( We have to get to the castle

(There is a forest in front of the castle

(There is a troll in the forest

(The troll is armed with a whole tree

We light the tree on fire)

We confuse the troll with riddles and escape.)

We traverse the forest)

(There is a moat in front of the castle

(We can't find bridge materials, but there's a shopkeeper who can sell them

(We don't have any money

...

We have money)

We buy the materials from a shopkeeper)

We construct a bridge to cross the moat)

We get to the castle )

So long as we close each problem before we move along, we've at least created a comprehensible and regular narrative.

Goalposts

Another bit of advice I've encountered is that each cycle of setback and solution must visibly move someone closer to a key goal. This is one of the inherently satisfying things about travelling from location to location "we need to get to Mount Doom" plots1: they come with built-in goalposts! The audience can see forward progress, which helps them feel like the story has momentum and direction.

Scott Pilgrim vs. The World and the Mega Man video game series both have one of my favorite invocations of this: just a numbered list of foes that need to be defeated. Defeat the 7 evil ex-boyfriends or defeat the 8 robot masters! That's clear, unambiguous progression! 2

Especially ones that come with a map!

A numbered Carnival of Killers is just straight up fun. If you're ever bored while running a D&D campaign, toss one of these in for instant spice.

6. World - mastering the new world, false victory, the goal achieved

Whereas the previous beat represents a phase of improvisation and adaptation, by the midpoint of the story our protagonist is beginning to feel more competent and in charge of the situation. They've finally figured things out.1

They've become so competent, in fact, that they're able to resolve the original goal that brought them here - and yet, with that goal achieved we're only at the midpoint of the story.

What gives?

Spoiler: no, they have not.

Framing The Character Arc in Terms of Wants & Needs

Often the Character Arc and dramatic question of a character (mentioned above) is framed in terms of the gap between what a character wants and what they need - a character may want to be fabulously wealthy, but need acceptance and community.1 Their "want" forms the goal that they chase and ultimately achieve at the midpoint of the story - their "need" forms the goal that they realize they needed to be chasing and ultimately achieve at the climax of the story.

Tragic stories often do this in reverse: characters get what they need at the midpoint of the story, then abandon it and chase what they want until the end of the story, ultimately leading to their downfall. Often the story's antagonist has this tragic arc, mirroring the hero's more positive arc through the story!

A reframing of this is "the big lie the character believes" - in this case the lie is "I need to be fabulously wealthy to be happy". I think the "want" and "need" framing is clearer and more useful, so I'm dunking the "big lie" here in a footnote. Sorry, K.M. Weiland.

7. Path - the cost of victory becomes apparent, gathering troubles

The universe cannot abide by a protagonist achieving their goals.

Trouble starts to mount, often caused by the friction between the protagonist's wants and needs. Our aforementioned "need to be fabulously wealthy" protagonist may find that their wealth and power actually isolates them, carrying them further away from their needs.

8. Curopal - the twist, betrayal, everything falls apart

Finally, that friction comes to a head and the protagonist's victory turns to dust.

Sometimes this involves an active twist or betrayal, but just as often this can be anything that's been building during the act.

Act 3.

In the third act, our job is to wrap the whole story up.

The Old World and the New World: Why Not Both?

One of the thematic goals of Act 3 is to create some sort of unified perspective between the old world and the new world.

This means that Act 3 can really bounce around between old world and new world.

Threats, too, can extend to both worlds.

8. Curopal - the twist, betrayal, everything falls apart

This sudden reversal of fortune leaves our protagonist in a bad position.

9. Blit - the darkest before the dawn, return to the familiar, a hope spot

Everything is lost. There is no possible route to victory here: our protagonist has lost everything. Anybody would wallow in misery in this situation.

At its very lowest, at the point where the low could not get any lower, often our protagonist has a brush with death itself: they die, or someone around them dies. Sometimes it's even permanent.

But something - something small - gives our protagonist the tiniest shred of hope. They can go on! Maybe it's a clever idea or plan, or the solution to the mystery they've been trying to solve all along.

10. Audient - the grand showdown, climax and apotheosis

This is the big moment. The big swell in the music, angels cheering from on high, a key change into a huge chorus.

In a stunning and dramatic reversal, our protagonist flips the script and comes out on top.

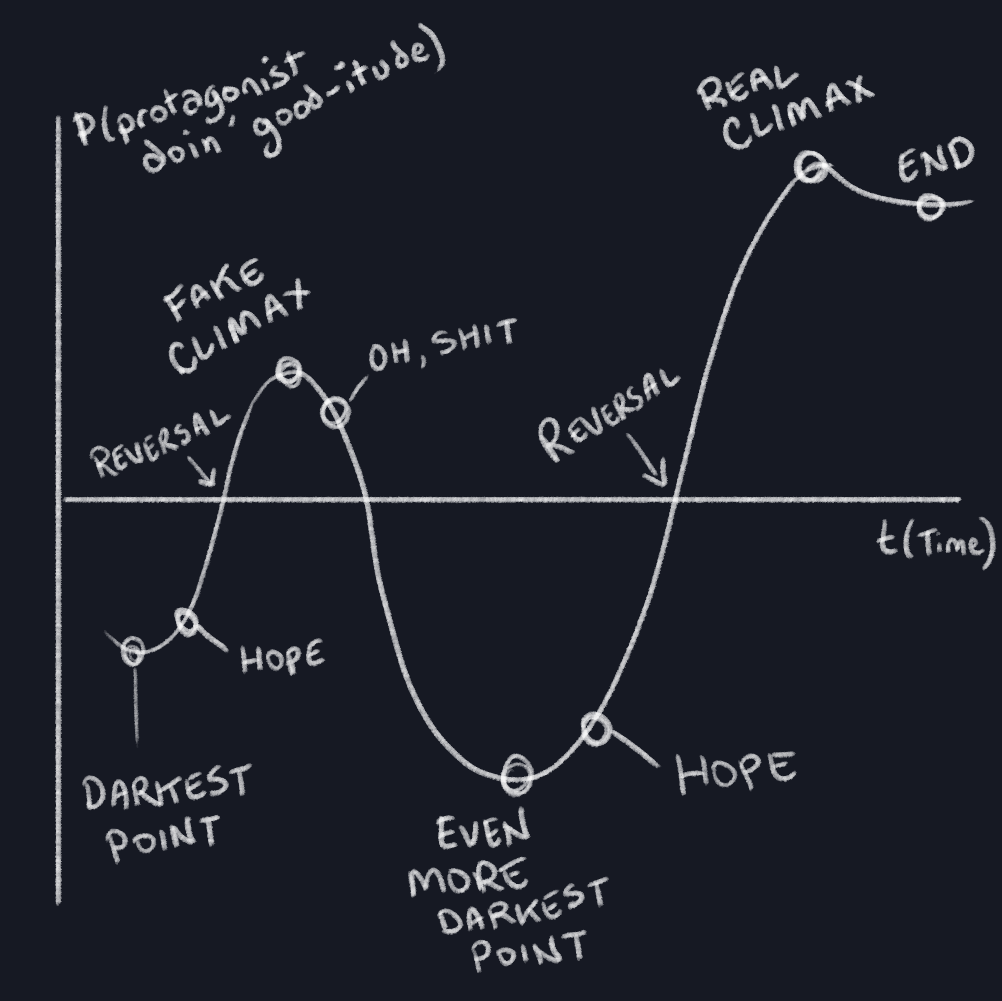

A Repeating Cycle of Death and Rebirth

This is one of the places where the linear nature of the Story Cycle struggles the most: many stories will take a couple of swings at the climax.

After what seems like the grand showdown and climax, we get another twist where everything falls apart!

This means that steps 8 through 10 might repeat a couple of times, hitting lower lows and higher highs each time:

11. Misk - master of both worlds, returning and becoming whole

Denouement. Wrap up.

If our protagonist finally reconciled their character arc - they found what they need rather than chasing what they want - now would be a great time to show them happy in a new, better status quo, the implication being that this one is going to be more permanent.

If their arc resolved tragically - they chased what they wanted and lost everything in the climax - now we focus on them miserable in a new status quo.1

If the protagonist didn't resolve their arc at all, what have you been doing all this time?

There's a bit of pleasing schadenfreude to watching the villain's miserable new status quo, if they survived.

Brick Joke

This is also a great time to wrap up any inconsequential loose threads. I'm enormously fond of stories that set up a Brick Joke early on in the plot and don't pay it off until the denouement, after the events of the whole story.

As a kind of hackneyed example of this, imagine our protagonists accidentally just ruining someone's bathtub in the course of their adventure. By the end of the adventure, the audience will mostly have forgotten the tub, but as a very final scene having the tub's owner encounter the mess: "Sacré bleu! My bathtub is ruined!"

I'm a simple man, I'm pretty sure that's funny.

12. Zariel - Beginning & End

The story is complete, at this point.

Once this story ends, another story will begin, the loop will continue, the wheel will keep turning.

Zariel is the context surrounding the story, the eternal loop of the story cycle.

This element isn't so much in the story as it is around the story.

How is the story framed? Who is the viewpoint character? Is the story first-person ("I went to the store"), third-person omniscient ("Ted went to the store"), the wildly rare second-person ("You went to the store"), or even the as-yet undiscovered fourth person ("A character representing all Teds across all universes went to every store, past, present, and future").

Is there a narrator? Is the narrator reliable? Is the narrator aware that this is a story?

This can mean "sequel hooks" - okay, the story is complete. What happens next?

Does this tie into a larger story?

This is particularly relevant in a sitcom-style model where the whole universe literally has to reset after most episodes, because episodes are written out of order by different people and all depend on the same shared universe.

A Dire Warning

As a reiteration of the dire warning in the characterization chapter, you might notice that each of the 12 spokes of the story wheel line up pretty well with the 12 characters described in the previous chapter.1

This is intended to be loose and evocative, however, not formulaic and prescriptive.

For example, Kiro, the sunny, optimistic archetype? Very easy to get to cross the threshold. Good choice to help someone else get across the threshold. If your story is struggling in this area, a Kiro might help. That doesn't mean you need to use all twelve characters.

In fact, that warning goes for the story cycle at large. It's also intended to be loose and evocative rather than formulaic and prescriptive. If you find yourself trying to hit a checklist of beats required by a formula, your writing is going to come out mechanical and soulless.2

I very badly hope you notice this.

like mine does